Publications by Geoff Hanmer: Managing Director of ARINA and Adjunct Professor of Architecture at the University of Adelaide

@geoffhanmer

The Australian: Higher Education Supplement

The Conversation

Refer also to the Conversation for Article Attributes, Creative Common Licensing and Disclosures

[Click Publication Titles below to Show/Hide]

Why universities may come to regret the costs of City Deals and private sector ‘solutions’

Universities have had few sources of capital funds since the Abbott government sidelined the Education Investment Fund in 2014. The loss of an estimated A$16 billion of income by 2023 due to the COVID-19 pandemic has simply added to this problem.

The City Deals process is one option, but for most universities it’s a poisoned chalice. A university will have to make a large financial contribution to the project and bears the risk of any cost overruns. These deals were conceived in the salad days prior to 2020 and now look decidedly wilted.

Read more: Think big. Why the future of uni campuses lies beyond the CBD

How do these City Deals work?

The Perth City Deal, for example, includes a $695 million project for Edith Cowan University. With the Commonwealth providing $245 million and the state government $150 million, ECU must stump up $300 million and hand over its perfectly serviceable Mount Lawley campus to the state government. The upshot is that the university will spend much more than would be needed to upgrade that campus for the dubious benefit of moving it 6km to the CBD.

The Australian Department of Infrastructure describes City Deals as “a genuine partnership between the three levels of government and the community to work towards a shared vision for productive and liveable cities”. The Perth deal is clearly a boost for the CBD and the Western Australian construction industry. The benefits to teaching or research at ECU are less easy to identify.

The Darwin City Deal commits Charles Darwin University (CDU) to a new campus in the Darwin CBD. CDU teaches 70% of its student load online, but it will end up with four campuses in Darwin with a combined capacity of well over 10,000 students to teach the 4,000 enrolled for on-campus study. The prospect of more students from China, which was a key component in planning for the project, has disappeared.

The deal required CDU to take out a $151.5 million loan from the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility (NAIF). While the interest rate is low, the capital component must be paid back.

Again, this project is a boost for the Northern Territory construction industry, but it may well reduce CDU’s capacity to spend on teaching and research. As a result of longstanding financial pressures, CDU has already sacked 77 staff and scrapped courses.

Read more: A fad, not a solution: 'city deals' are pushing universities into high-rise buildings

Another option is to spend nothing on infrastructure. The University of Adelaide has announced a complete halt to such spending for the foreseeable future. It still plans to attract “top talent” with its ageing facilities. Quite how this will work is unexplained.

Developers are in it for the profits

Other universities have struck deals with developers. These can range from selling university assets and leasing them back, or signing up to a long-term lease on new purpose-built space using a special purpose vehicle (SPV), doing developments using university land, or other financial wizardry.

Charter Hall, a real estate investment company, has signed up Western Sydney University to several deals with a combined value of around a billion dollars. A new $350 million campus is being built in the CBD of Bankstown.

Charter Hall has openly said its aim is to create a new asset class in university buildings and campuses. This approach effectively privatises campus assets, nearly all of which were paid for with public money and charitable donations.

Western Sydney University is selling a newly built neighbourhood shopping centre and an adjoining residential development site. This was developed with Charter Hall on land controlled by the university, which says: “The Caddens Corner project is part of the Western Growth strategy, reshaping the University’s campus network, and allowing the University to maximise its investment in the core university activities of teaching, engagement and research.”

This is an interesting proposition, as teaching, engagement and research are all essentially operational, not capital, costs. In other words, the university is selling public assets to fund recurrent costs while planning to have 13 campuses to educate not many more students than Macquarie University, which has one.

Read more: 3 planning strategies for Western Sydney jobs, but do they add up?

In Melbourne, Swinburne University has put a seven-storey office building on Flinders Lane back on the market just one year after buying it for $44 million. In June, RMIT University in Melbourne brought forward plans to offload a 14-storey strata property on Bourke Street for more than $120 million and lease it back for five years.

A good time to borrow and build

Certainly, getting a developer to build a facility and lease it back to the university will reduce the need for capital. For similar reasons, a low-income household might choose a rental purchase arrangement to get a flat-screen TV. But like any rental purchase agreement, the short-term benefits pale in comparison to the long-term costs.

And universities are certainly about the long term. Four universities in Australia are more than 125 years old and they are youngsters compared to Harvard (385), Leiden (436), Oxford (925) or Bologna (933).

Read more: A century that profoundly changed universities and their campuses

Another option for universities is to borrow money from a bank. If the universities can’t afford to do that, then they can’t afford to get developers to borrow money on their behalf and build them buildings while the developers also make a profit. There is no secret sauce and definitely no magic pudding.

Borrowing to fund the replacement or refurbishment of buildings at the end of their economic life is financially prudent providing benefits outweigh costs. University leaders might need to learn how to resist the temptation to make every building an “icon”, but capital investments to support teaching and research are rational and responsible. With interest rates as low as they will ever be and building costs a long way below the peak of the next cycle, now is an ideal time to build.![]()

Geoff Hanmer, Honorary Professional Fellow, Faculty of Design, Architecture and Building, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

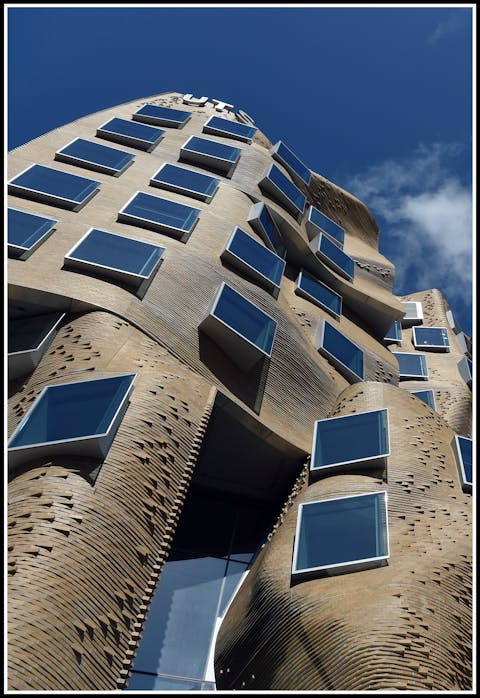

Think big. Why the future of uni campuses lies beyond the CBD

This is the second of two articles on the past and future of the university campus.

The “dreaming spires” of Oxford University that Matthew Arnold romanticised in 1865 still have a powerful grip on our image of the university. Nevertheless, the university town is part of the past. A key reason for this is the expense of developing facilities on a confined site, particularly in a heritage setting.

Read more: A century that profoundly changed universities and their campuses

The new Beecroft physics building at Oxford is ten storeys high but five are below ground because of government-imposed height restrictions. Unfortunately, this configuration requires a large percentage of floor space to be devoted to stairs, lifts and ventilation ducts. Although the building costs about £5,500 (A$9,840) per square metre of gross floor area, the cost per usable square metre is an eye-watering £15,000. That’s about double the going rate for this type of building on a large-area campus.

The new Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge will cost £300 million for similar reasons.

Expansive campuses dominate overseas

In the 1970s, the University of Heidelberg moved from its site in the town of Heidelberg to a new 112-hectare campus on the north bank of the Neckar River. This enabled the university to develop new space, particularly laboratory space, at economical cost. In the decade after 2007, Heidelberg rose from between 51st and 75th in Science on the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) to 39th. Oxford slipped from tenth to 13th and Cambridge from fourth to seventh.

Of the No. 1 universities in the 54 subjects tracked by the ARWU, including humanities subjects, 84% occupy large campuses of 50 hectares or more.

The most interesting campus development in the world at the moment is the University of Paris-Saclay. The French government is grabbing the best bits of the University of Paris and assembling them into a super research university. Intended to rank within the ARWU top ten, it is already first in mathematics and 14th overall.

Read more: Why France is building a mega-university at Paris-Saclay to rival Silicon Valley

Paris-Saclay is located on 189ha of farmland south of Paris, close to a railway station. It’s the classic large-area campus. Next to the campus lots of cheap land has been made available for startup companies that will be spun out of the university or existing companies that relocate to use its research or facilities.

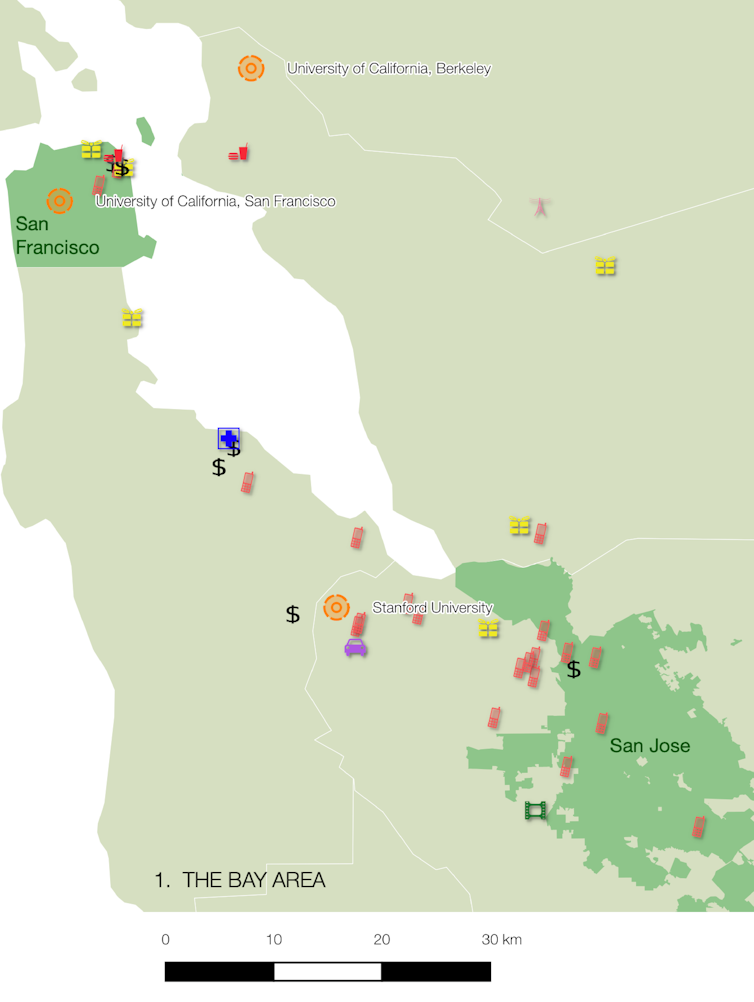

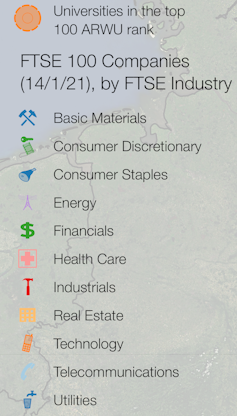

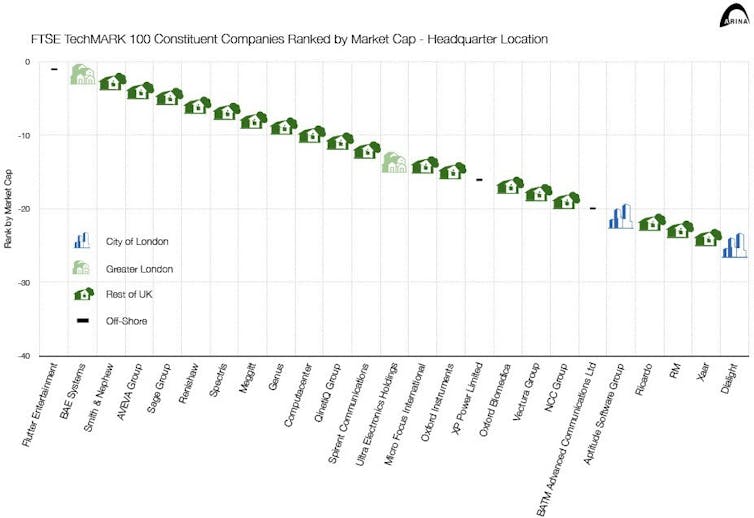

It is another attempt to recreate Silicon Valley, and there’s every reason to try. As part of research by ARINA, an architectural firm specialising in higher education, community and public design, a simple mapping project shows 67% of the market capitalisation of US Fortune 500 Tech companies is located in the triangle between San Francisco, Oakland and San Jose. Two top ten universities, Stanford and UC Berkeley, are also located there.

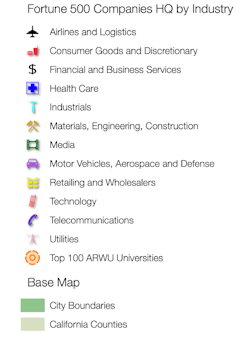

Similarly, in the UK, a belt of high-tech and new-economy industries stretches from Bristol through Oxford, Milton Keynes, Bedford and Cambridge. Also located here are the ARWU top 100 universities of Bristol, Oxford and Cambridge and the nearly-there Warwick.

More than 50% of the market capitalisation of companies in the FTSE Tech 100 are also located in this area. Only 17% of companies in this index are located in Greater London, and none in central London.

UCL (formerly University College London) is building a new large-area campus at UCL East on the former London Olympics site in Hackney. Its aim is to ease pressure on the 9.7ha UCL campus in Bloomsbury and to provide opportunities for partners to be located close by.

What about Australian developments?

In Australia, our most recent efforts at building campuses are a mixed bunch.

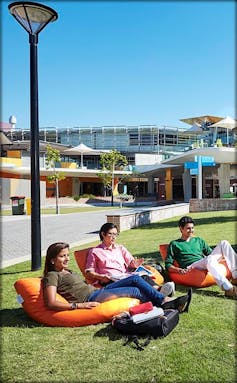

The new Western Sydney “Aerotropolis” and the new University of Melbourne campus at Fishermans Bend in Melbourne are plausible because they are expansive campuses with land for partners to invest in nearby facilities. Delivering low and mid-rise buildings on less expensive land served by public transport seems like a good bet.

Macquarie University’s role in the Macquarie Park business and innovation district in Sydney and Deakin’s Waurn Ponds campus in Geelong have successfully attracted private investment and provide evidence that this concept can work.

Other universities have demonstrated how to mess this up. UNSW built a new building to accommodate a commercial partner in photovoltaics. Unfortunately the commercial partner then dropped out. The university was left with a large bill and an empty building.

The key lesson of this, and many other initiatives, is for the university (and government) to deliver attractive intellectual property but to avoid investing in building facilities that the private sector might occupy at some unspecified time in the future. In other words, don’t build and expect them to come.

There are proposals to move the University of Tasmania’s Sandy Bay campus to the Hobart central business district, to create a new CBD campus in Darwin for Charles Darwin University and to shift Edith Cowan University’s Mt Lawley campus into the Perth CBD. As I have argued before, all these proposals are a response to a trend encouraged by the development industry rather than a rational response to issues confronting the higher education sector.

Read more: A fad, not a solution: 'city deals' are pushing universities into high-rise buildings

Look where world-changing products were born

ARINA research suggests the economy in CBDs is increasingly focused on banking, finance, insurance, property development, accounting and consulting – rentier industries built on income from property or securities that depend on government rather than research to prosper. These are not industries that need a helping hand to grow and they are not industries that initiate change. Putting university campuses physically next to them is pointless.

With its key product, the iPhone (launched in 2008), Apple has probably done more to change the world than any other corporation in recent times. It has done so from a campus in Cupertino, roughly midway between San Jose and Stanford University.

The research that has produced the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine originated in Mainz, Germany, population 217,000. The research for the AstraZeneca vaccine was carried out in the outskirts of Oxford, UK. Moderna’s research facilities are in Cambridge, Massachusetts, near MIT.

Most of the things that have made a difference start in sheds (Boeing and Douglas aircraft companies) or garages (Apple, Google and Hewlett Packard), or cheap office space (Intel).

I start and finish these articles with the observation that it costs about half as much per delivered square metre to build on a large-area campus. Low to mid-rise buildings have more usable space per gross sq m, are more sustainable because they use less embodied energy and are inherently more adaptable.

A very large campus provides space to develop facilities that will be required as research evolves over time. The surrounding land is cheaper and therefore more attractive to the firms that might draw on university research. That’s the “secret” of both Silicon Valley and the UK high-tech belt. And it’s why the University of Paris-Saclay will work.

In Australia, we should contemplate why the Bay Area is so successful, learn from the example of the University of Paris-Saclay and rethink our obsession with CBD campuses.![]()

Geoff Hanmer, Adjunct Professor of Architecture

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A century that profoundly changed universities and their campuses

This history of the development of universities is the first of two articles on the past and future of the campus. This is a long read, so set aside the time to read it and enjoy.

Once the first atomic bomb exploded on July 16 1945 in New Mexico, the world would never be the same again. Scientists and engineers had turned an obscure principle into a weapon of unprecedented power. Los Alamos, the facility where the bomb was designed, was run by the University of California.

This was a turning point for universities. As they increasingly focused on scientific research, the role of universities worldwide – and their campuses – changed.

Before the first world war, the largest investment on most campuses was the university library. After the second world war, investment shifted decisively to laboratories and equipment.

A key reason for the increasing focus on university research was the lessons of the first world war. After the war, governments of rich countries took an increasingly interventionist role in directing and encouraging the research and development of artificial materials, weapons, defences and medicine. Universities or institutes associated with universities did much of this work.

Read more: Universities and government need to rethink their relationship with each other before it's too late

By 1926, the Council for Science and Industrial Research, the predecessor to the CSIRO, and the organisation that would become the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) had been founded in Australia.

A gradual turn towards research

In the UK, many of the older universities were not that keen on applied research. Chemistry, engineering and physics were taught at Oxford between the wars, but by 1939 the chemistry cohort was just over 40 students, of whom “two or three were women”.

It wasn’t until 1937 that Oxford drew up a plan to develop the “Science Area” with new buildings, but in that same year, the university also agreed to reduce its size to avoid a fight with the Town over “further intrusion on the Parks”.

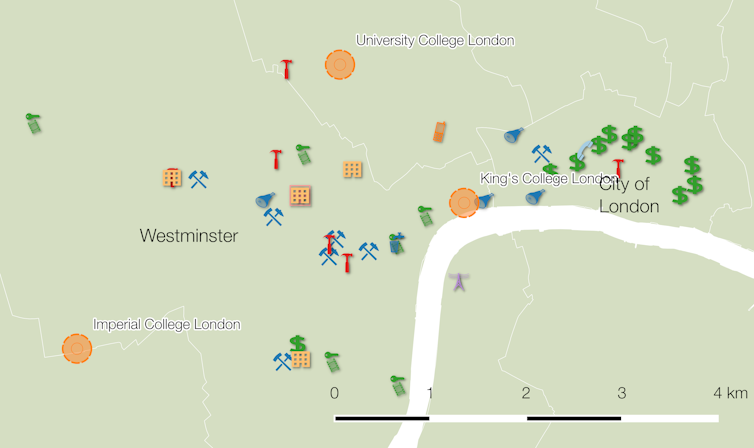

Facilities at Cambridge for physical sciences were slightly better, but not by much, despite its historical focus on mathematics. The Cavendish laboratory in which the New Zealander Ernest Rutherford discovered in 1911 that the atom had a nucleus was small, dark, damp and ill-equipped.

This relative lack of interest in experimental sciences at Oxbridge was unhelpful for science research in Australia, because our six small state-run universities tended to follow their lead. As an indication of its priorities, the University of Adelaide built its humanities buildings in stone and its much more modest science facilities in brick.

Nobel laureate and University of Adelaide Professor W.H. Bragg carried out his pioneering experiments on X-ray crystallography in Adelaide during 1900 to 1908 in a converted storeroom in the basement of the Mitchell Building. His lab is now a storeroom again.

The post-war transformations

The application of university research had been a German strength since well before the first world war with the rise of the Humboldtian model of higher education, which favoured research over scholarship. A key reason the Allies prevailed in 1945 was that the United States in particular rapidly improved its capacity to carry out and apply research, based on the Humboldtian model.

In 1917, MIT established a naval aviation school. The University of Washington soon followed MIT’s example.

This decision had a direct bearing on the success of the Boeing company following construction of the Boeing wind tunnel at the University of Washington’s Seattle campus in 1917. It led directly to the development of advanced aerodynamics for the Boeing 247 of 1933, which provided the template for all subsequent commercial airliners.

The Australian university system between the wars offers no such exemplars. The focus on applied research was foreign to the prevailing university culture in Australia at the time. As Hannah Forsyth writes in A History of the Modern Australian University, not until the 1940s did “scholarly esteem began to move away from ‘mastery’ of disciplines towards the discovery of new knowledge”.

New research facilities and new campuses

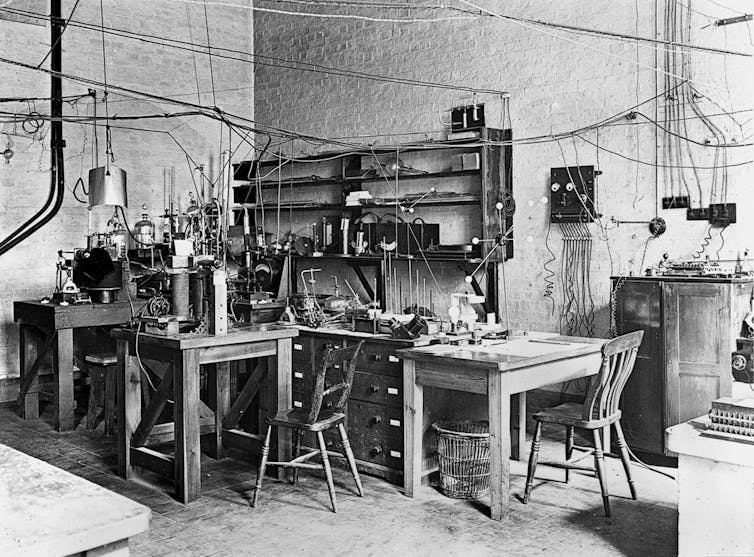

New technologies led to a host of new post-war industries, including commercial aviation, television, plastics, information technology (IT) and advanced health care. The demand for skills to operate these new industries was the primary driver of an explosion in university enrolments.

University science research in Australia only got a serious start in 1946 with the foundation of the Australian National University (ANU) and the Commonwealth Universities Grants Committee, which became the Australian Research Council (ARC).

As Robert Menzies, the prime minister from 1949-66, later wrote:

The Second World War brought about great social changes. In the eye of the future observer, the greatest may well provide to be in the field of higher education.

In Australia, about 80% of our universities have been founded since the second world war. The growth of the sector has been startling.

Read more: Australia doesn't have too many universities. Here's why

All of the institutions founded during the Menzies era were sited on large campuses in the suburbs or beyond. Although mainly Commonwealth-funded, they were designed and delivered by state public works authorities to tight budgets on land provided largely by state governments. UNSW, Monash, Griffith, La Trobe, Flinders and WAIT (now Curtin) share a heritage of economical buildings on large parcels of land.

The key reasons for this approach were to minimise cost and maximise capacity for growth and change. Low to medium-rise buildings on land surplus to state needs maximised bang for buck. Development costs per square metre of building were about half that of a campus in the central business district (CBD) of cities.

This was not a new discovery. The universities of Stanford, Berkeley, Caltech, Tokyo, Wisconsin and Peking, all founded in the 19th century, used this model for similar reasons.

Fortunately, the states were generous with land they didn’t need. Of all the universities built in the Menzies era, only UNSW with 39 hectares has a significant land area constraint. The other universities have at least 50ha and several have well over 100ha. This has given them some headaches, but also lots of options.

Research by ARINA, an architectural firm specialising in higher education, community and public design, shows that virtually all universities built since 1949 – that’s more than 90% of universities in the world – have large campuses with densities less than 500 students per hectare. The University of Bath, built in 1966, is typical of post-war UK universities with 59ha and 16,000 students in 2021, less than 300/ha.

The same is true even in small city-states such as Hong Kong and Singapore. The National University of Singapore has a campus of about 140ha with 37,000 students (264/ha) and Hong Kong University of Science and Technology has 55ha with 11,000 students (200/ha).

Most new universities in Europe, Asia, India and the Middle East still rely on the large campus model. The University of Paris-Saclay, for example, is being built on 189ha of former farmland 15km south of the Paris orbital motorway.

Broad-acre campuses are popular with students as measured by surveys of educational experience such as the Australasian Survey of Student Engagement (AUSSE) and the US National Survey of Student Engagement (NESSE). The most popular campuses in Australia are Bond, New England, Griffith and Notre Dame. RMIT and UTS, the highest-ranked CBD campuses finish in the middle of the pack, a long way behind the leaders. A similar phenomenon can be seen in the UK and the US.

Read more: Looking beyond the sandstone: universities reinvent campuses to bring together town and gown

Campus model goes corporate

The ARINA research indicates broad-acre campus models have also become increasingly part of the physical organisation and accommodation of many commercial operations.

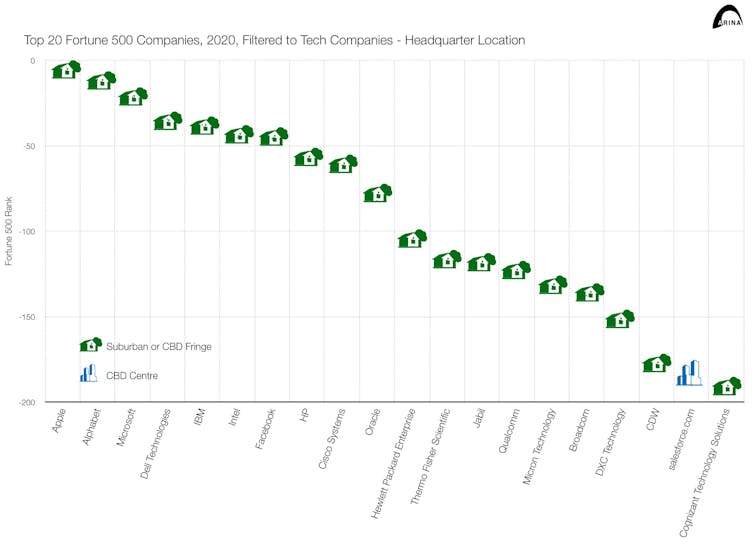

In 2020, 63% of the top 30 US Fortune 500 index and 87% of the top 30 tech companies in the index were located in suburban and extra-urban settings, mostly campuses. This includes well-known tech companies such as Apple, Alphabet, Facebook, Tesla and HP, but also less obvious candidates such as Walmart, Exxon Mobil and Amazon.

In the UK, 28% of all FTSE 100 companies and 54% of FTSE Techmark 100 companies by market capitalisation are based outside greater London.

The reasons for this are straightforward: capital and operating costs for research-based firms are lower outside a CBD. While some Australian universities are choosing to head into the city, much of the new economy appears to be heading for the suburbs. It’s happening for the same reason that universities started to migrate there over a hundred years ago.

Read more:

The rise of the corporate campus

![]()

Geoff Hanmer, Adjunct Professor of Architecture

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

News of the collapse of the Grocon empire is greatly exaggerated

Geoff HanmerGrocon, the Australian construction empire that grew from the family concreting business started by Luigi Grollo in Melbourne in 1948, is on its last legs.

But Grocon, the privately held property development empire headed by Luigi’s grandson Daniel Grollo, will continue to operate.

Media outlets have breathlessly reported Grollo’s announcement that Grocon’s construction business is insolvent, meaning it is no longer able to pay its debts, and that external administrators have been called in (as the law requires) to sort out if the business can be sold or its assets liquidated to pay off at least some of what is owed.

The Grocon group, though, is more than a construction business, having found better money-making opportunites in property development and being a landlord. It is a web of many legal entities and holding companies.

Exactly how much of the web is being put into administration is not yet clear – as a private company, disclosure requirements are fewer than those for public companies (listed on a stock exchange).

But based on Grocon’s track record – and common practice in the Australian building industry – the most likely upshot is that Grocon will cut its losses on ailing entities without affecting the profitable parts of the greater empire.

One thing seems sure, though. Daniel Grollo and other executives will not be at risk of losing their homes and livelihoods. The real losses will be felt by others.

Development beats construction

Luigi Grollo’s construction business began with pouring concrete on small projects. As time went by its projects got bigger. In the 1970s it moved beyond building for other entities into property development on its own account – acquiring land, gaining development approval, building and then selling or leasing the finished product.

Development, which requires a certain amount of vision, access to capital and solid political connections, is the route to making serious money.

Read more: Federal parliament just weakened political donations laws while you weren't watching

Construction, by comparison, provides limited opportunities for a big payday and plenty of opportunities to make a hash of it.

The landscape for Australia’s “Tier 1” builders – the contractors able to take on the largest projects – has been poor for several years.

Lendlease, for example, announced in December 2019 it was selling its engineering construction business to Spanish infrastructure conglomerate Acciona. The sale followed huge losses on projects such as the Melbourne Metro underground rail project and Sydney’s NorthConnex motorway tunnel project.

John Holland, the builder of Melbourne’s West Gate Tunnel and the Sydney Metro light-rail project, lost A$60 million in 2019. CIMIC Group (previously known as Leighton) made a net loss of A$1 billion.

Grocon’s Barangaroo stoush

The stated catalyst for Grocon’s announcement about its construction business is a legal dispute with Infrastructure New South Wales, the state authority overseeing the development of Sydney’s Barangaroo precinct. Different companies are developing and building different parts of the project.

In 2018 Crown Resorts and developer Lendlease fought and won a legal case against Infrastructure NSW over fears buildings being built by a Grocon-led consortium as part of the “Central Barangaroo” precinct would block harbour views from Crown’s casino hotel and Lendlease’s high-rise apartments in the “Barangaroo South” precinct.

Grocon subsequently pulled out (selling its interests to Chinese partner Aqualand). It is suing Infrastruture NSW for A$270 million in compensation for not informing Grocon it needed to factor in sight lines from the Crown Resorts and Lendlease buildings.

Grollo blamed Infrastructure NSW for “forcing our hand to place the construction business into administration”:

While I have spoken before about moving Grocon away from the construction business model to new initiatives such as build to rent, I did not want to call in administrators.

But Grollo has said such things before.

In October last year Grocon put two subsidiaries into insolvency over a dispute with commercial landlord Dexus involving A$28 million in unpaid rent for space leased in Brisbane’s 480 Queen Street building.

Grollo also declared he was doing this reluctantly but had been forced into it.

Australian Securities and Investments Commission records indicate 27 Grocon entities have been deregistered or cancelled since about 2006. That leaves, by my count, 31 registered companies. How many of these will now be placed in administration is unclear.

Read more: These private companies pay less tax than we do – but reasons remain unclear

A notorious industry practice

The construction industry is notorious for the use of insolvency and administration mechanisms, dominating the statistics out of all proportion to its share of the economy.

Many in the industry see it as a normal business practice.

It’s a cost-effective solution, but it leaves subcontractors and other suppliers owed money in the lurch. It creates waves of bankruptcies among smaller businesses – electricians, plumbers, plasterers and so on – who have often secured business loans with their homes. Many are left destitute. It helps explain the industry’s high suicide rate.

Read more: Is illegal phoenix activity rife among construction companies?

Privatising profits, socialising losses

Is it right for a big operator with substantial resources to slice and dice its operating companies to ensure it continues to prosper while its subcontractor and consultant creditors are ruined?

The construction union – with which Grocon has long battled – has called for a national scheme to compensate subcontractors when a head contractor goes bust.

But this is an invitation to continue to privatise profits and socialise losses.

The first step governments could take is to adopt procurement policies using value-based assessments rather than just choosing tenders based substantially on price.

They should also not try to transfer unmanageable risks to constructors and consultants, including setting unachievable budgets and programs.

This would encourage contractors to submit honest tenders and deliver quality projects without exploiting the smaller players they rely on.

Effective monitoring of downstream activities, including payments to subcontractors, is also vital.

If we are going to have a construction industry that does not rely on the public purse to pick up the pieces, we don’t need another inquiry or royal commission. We do need a co-ordinated effort to fix the obvious problems, including effective laws to stop insolvency and administration being standard business practice.

Administrators and liquidators should have readier access to the assets of other companies in a group and also the assets of directors.![]()

Geoff Hanmer, Adjunct Professor of Architecture

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

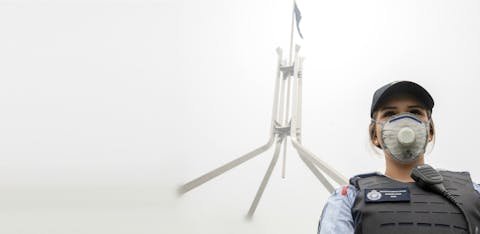

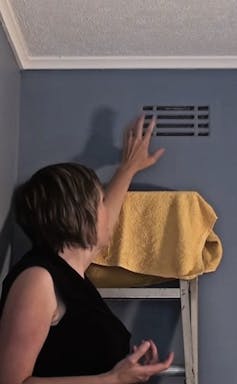

Many of our buildings are poorly ventilated, and that adds to COVID risks

The virus that causes COVID-19 is much more likely to spread indoors rather than outdoors. Governments are right to encourage more outdoor dining and drinking, but it is important they also do everything they can to make indoor venues as safe as possible. Our recent monitoring of public buildings has shown many have poor ventilation.

Poor ventilation raises the risks of super-spreader events. The risk of catching COVID-19 indoors is 18.7 times higher than in the open air, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Read more: Poor ventilation may be adding to nursing homes' COVID-19 risks

In the past month, we have measured air quality in a large number of public buildings. High carbon dioxide (CO₂) levels indicate poor ventilation. Multiple restaurants, two hotels, two major shopping centres, several university buildings, a pharmacy and a GP consulting suite had CO₂ levels well above best practice and also above the absolute maximum mandated in the National Construction Code.

Relative humidity readings of less than 40% associated with both heating and cooling air are also of concern. Evidence now suggests low humidity is associated with transmission.

If anyone had COVID-19 in these environments, particularly if people were in them for an extended period, as might happen at a restaurant or pub, there would be a risk of a super-spreader event. Less than 20% of individuals produce over 80% of infections.

Read more: A few superspreaders transmit the majority of coronavirus cases

Many aged-care deaths were connected

It appears a relatively small number of super-spreader events, probably associated with airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, were responsible for most of the deaths in Victorian aged-care facilities.

Of the 907 people who have died of COVID-19 in Australia, 746, or 82% of COVID-19 deaths, were associated with aged care. In Victoria, there were 52 facilities with more than 20 infections. Three had over 200 infections. As a result, 639 of the 646 aged care residents who died in Victoria were located in just 52 facilities.

But official advice hasn’t changed

Aged-care operators and the states based their infection control on the advice of the Commonwealth Infection Control Expert Group (ICEG). As of September 6, the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Residential Aged Care Facilities Plan for Victoria stated:

Coronavirus (COVID-19) is transmitted via droplets, after exposure to contaminated surfaces or after close contact with an infected person (without using appropriate PPE). Airborne spread has not been reported [our emphasis] but could occur during certain aerosol-generating procedures (medical procedures which are not usually conducted in RACF). […] Respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette, hand hygiene and regular cleaning of surfaces are paramount to preventing transmission.

In early August, more than 3,000 health workers had signed a letter of no confidence in ICEG. The letter noted that aerosol transmission was causing infections in medical staff, many of whom worked in aged-care facilities.

On September 7, we wrote to the federal aged care minister, Richard Colbeck, drawing attention to our August 20 article in The Conversation, which referenced a July 8 article in Nature. The Nature article identified an emerging consensus that aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is probable in low-ventilation environments.

Read more: How to prevent COVID-19 ‘superspreader’ events indoors this winter

The director of the Aged Care COVID-19 Measures Implementation Branch wrote back on Colbeck’s behalf on September 28 saying:

Current evidence suggests COVID-19 most commonly spreads from close contact with someone who is infectious. It can also spread from touching a surface that has recently been contaminated with the respiratory droplets (cough or sneeze) of an infected person and then touching your eyes, nose or mouth.

In other words, Commonwealth authorities were still playing down the significance of airborne transmission nearly two months after the letter of no confidence was sent to ICEG and three months after the article in Nature. By the end of September, Victorian aged-care facilities had reported over 4,000 cases of COVID-19, about half of them in staff.

On October 23, ICEG was still saying:

There is little clinical or epidemiological evidence of significant transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) by aerosols.

Focus on the ‘3 Vs’ to reduce risks

The key thing we need to do until a vaccine is rolled out is to try to prevent indoor super-spreader events. According to the University of Nebraska Medical Centre, we should remember the “three Vs” that super-spreader events have in common:

Venue: multiple people indoors, where social distancing is often harder

Ventilation: staying in one place with limited fresh air

Vocalization: lots of talking, yelling or singing, which can aerosolize the virus.

Measuring indoor ventilation is quick and easy using a carbon dioxide detector. Any CO₂ reading of over 800 parts per million is a cause for concern – the level for air outside is just over 400ppm.

There is no excuse for governments, health authorities and building owners not to monitor ventilation levels to help ensure members of the public are as safe as is reasonably practicable when indoors.

There is also no excuse for the Australian Building Control Board not to change the National Construction Code to require fall-back mechanical ventilation systems be fitted and CO₂ and humidity monitored in all buildings frequented by the public, particularly aged-care facilities.

With the knowledge we have now and a low rate of community infection, Australia should be able to make it through to vaccine roll-out with relatively few further infections and deaths. But that depends on being vigilant about the quality of ventilation indoors and the associated possibility of super-spreader events. This is especially important in aged-care facilities and quarantine hotels.

It’s probably a good idea for us all to open the windows and let the fresh air in.![]()

Geoff Hanmer, Adjunct Professor of Architecture and Bruce Milthorpe, Emeritus Professor, Faculty of Science, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A fad, not a solution: 'city deals' are pushing universities into high-rise buildings

Let’s talk about “city deals”. The Australian government is.

Its department of infrastructure website describes them as “a genuine partnership between the three levels of government and the community to work towards a shared vision for productive and liveable cities”.

The idea comes from the UK. There they award extra funding and special decision-making powers to local authorities who can demonstrate they will use them to boost economic growth.

So far Australia has had eight city deals, in Townsville, Launceston, western Sydney, Darwin, Hobart, Geelong, Adelaide, Perth and southeast Queensland.

This announcement about the western Sydney deal from federal urban infrastructure minister Alan Tudge and NSW minister Stuart Ayres is typical:

The Western Sydney Aerotropolis and Western Sydney International (Nancy-Bird Walton) Airport will attract infrastructure, investment and skilled jobs, and the benefits will flow into health and education, retail, hospitality and industrial activities that will power the region.

It’s one of 22 such announcements about the Western Sydney deal in the past two years.

The deal no vice-chancellor can refuse

Whatever their merits as a tool for planning, city deals are useful for making announcements about jobs, and also for spending money in electorates in which the government takes a special interest.

In western Sydney, four universities – one of them the University of Newcastle, which is hundreds of kilometres away – are being funded to develop a “Aerotropolis Multiversity”.

Read more: City Deals: nine reasons this imported model of urban development demands due diligence

City deal funding is funding no university can resist, in part because it is now about the only way they can get money from the federal government for buildings.

The new Perth city deal requires Edith Cowan University to relocate to the central business district to “kickstart major projects in the city centre”.

It comes at an eye-watering cost of A$695 million. The university has to find $300 million. The federal government will provide $245 million.

The Western Australian government might come out ahead. It will contribute a $50 million CBD site it has had problems selling and take possession of the university’s Mt Lawley campus, just 5 kilometres north of the CDB, which it can use to expand the adjacent high school, selling what’s left for medium-density housing.

It has promised to use the proceeds to “underwrite” $100 million of the university’s costs, although whether this will be a loan or a grant is not clear.

Instead of being in a spacious campus that needs some renovation, 10,000 students will be in a vertical city building of the kind the University of Technology Sydney no longer uses for teaching, because of the difficulty of moving students between floors.

City buildings from Perth to Launceston

The first city deal was in Launceston. This involves moving part of the University of Tasmania’s campus from the suburb of Newnham to Inveresk, a site 5 km closer to the centre of Launceston.

It has many similarities to the Perth city deal, not the least being the university will have to do most of the heavy lifting, including bearing the risk of cost overruns.

There are rosy projections that the new site will attract more students, including internationals, but they run counter to the experience of the university’s School of Architecture and Design, which has experienced a catastrophic decline in enrolments despite being at Inveresk for many years.

In another part of the “Northern Transformation” project, the University of Tasmania is moving its Burnie operation from a 25-year-old campus at Mooreville Road 2 km to a new $85 million campus at West Park.

All up, the Northern Transformation project will cost the University of Tasmania more than $300 million, which at the moment it does not have.

Darwin is getting yet another CBD campus

A similar story is playing out in Darwin, where a new CBD campus for Charles Darwin University is being delivered 14 km from its main campus at Casuarina.

There the aim is to create an iconic building “that links city-based elements of CDU to each other and to various parts of the city, and offers the potential to reimagine the CBD with the university at its heart”.

What’s odd is that Charles Darwin University already has a CBD campus, organised in a deal with a local developer. It hasn’t met its student growth targets, mainly because it lacks the things needed to attract students, including a decent library, cheap places to eat and affordable accommodation.

The new CBD campus will be better than that, but the vastly more efficient option of simply redeveloping the main Casuarina campus and dumping the failed existing city campus wasn’t on the table.

While the Darwin CBD campus will generate jobs during construction, and the territory government will be overjoyed to be getting some cranes back on the Darwin skyline, the benefit for the university is harder to identify.

Funding ought to be needs-based

I am not against funding university redevelopments, far from it. Many of Australia’s university buildings are old and in need of updating.

The University of Tasmania, Charles Darwin University, Edith Cowan University and Western Sydney University, among others, enrol less of the international students that have allowed other universities to fund the maintenance and redevelopment of their buildings. Charles Darwin University and the University of Tasmania are the only universities in their states.

But the City Deal process is forcing universities to move into CBDs to get funds, whether it makes sense or not.

Read more: Why is the Australian government letting universities suffer?

Evidence suggests that CBD campuses are a fad, not a solution. Campuses in tall buildings cost about twice as much per delivered square metre as low to medium rise sites and CBD buildings lack the long-term development flexibility of a campus.

Most importantly, undergraduate students don’t much like them. They lack parking spaces, they often lack child-care facilities, students are forced to cram into lifts to move between classes, and they are not near cheap accommodation.

Students prefer space to height

The campuses popular with students around the world tend to be about 5-10 km from a CBD and have 5,000 to 20,000 students, with a high proportion living on campus.

Bond, the University of New England and Griffith University are good Australian examples. Leiden, Bath, Lancaster and Stanford are overseas examples.

It is sometimes said CBDs attract students, particularly international students, but most of Australia’s biggest and most successful universities are located on the city fringe or in suburbs.

Read more: 3 ways the coronavirus outbreak will affect international students and how unis can help

Few successful research universities are located in the centre of cities. Of the top 100 research universities in the world, as measured by the Academic Ranking of World Universities, only a handful are in CBDs, and usually only because the CBD engulfed them.

The best research comes out of large campuses, rather than single buildings.

The best-value university projects ought to be the ones that get funded rather than those that have the side benefit of allowing politicians to (repeatedly) claim they are “revitalising” cities.

But that would require paying attention to universities for their own sake, something the government appears reluctant to do.![]()

Geoff Hanmer, Adjunct Professor of Architecture

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Poor ventilation may be adding to nursing homes' COVID-19 risks

Geoff Hanmer and Bruce Milthorpe, University of Technology SydneyOver 2,000 active cases of COVID-19 and 245 resident deaths as of August 19 have been linked to aged care homes in Victoria, spread across over 120 facilities. The St Basil’s cluster alone now involves 191 cases. In New South Wales, 37 residents were infected at Newmarch House, leading to 17 deaths.

Why are so many aged care residents and staff becoming infected with COVID-19? New research suggests poor ventilation may be one of the factors. RMIT researchers are finding levels of carbon dioxide in some nursing homes that are more than three times the recommended level, which points to poor ventilation.

An examination of the design of Newmarch in Sydney and St Basil’s in Melbourne shows residents’ rooms are arranged on both sides of a wide central corridor.

The corridors need to be wide enough for beds to be wheeled in and out of rooms, but this means they enclose a large volume of air. Windows in the residents’ rooms only indirectly ventilate this large interior space. In addition, the wide corridors encourage socialising.

If the windows to residents’ rooms are shut or nearly shut in winter, these buildings are likely to have very low levels of ventilation, which may contribute to the spread of COVID-19. If anyone in the building is infected, the risk of cross-infection may be significant even if personal protective equipment protocols are followed and surfaces are cleaned regularly.

Why does ventilation matter?

Scientists now suspect the virus that causes COVID-19 can be transmitted as an aerosol as well as by droplets. Airborne transmission means poor ventilation is likely to contribute to infections.

A recent article in the journal Nature outlines the state of research:

Converging lines of evidence indicate that SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, can pass from person to person in tiny droplets called aerosols that waft through the air and accumulate over time. After months of debate about whether people can transmit the virus through exhaled air, there is growing concern among scientists about this transmission route.

Read more: Is the airborne route a major source of coronavirus transmission?

Under the National Construction Code (NCC), a building can be either “naturally ventilated” or “mechanically ventilated”.

Natural ventilation requires only that ventilation openings, usually the openable portion of windows, must achieve a set percentage of the floor area. It does not require windows to be open, or even mandate the minimum openable area, or any other measures that would ensure effective ventilation. Air quality tests are not required before or after occupation for a naturally ventilated building.

Nearly all aged care homes are designed to be naturally ventilated with openable windows to each room. In winter most windows are shut to keep residents warm and reduce drafts. This reduces heating costs, so operators have a possible incentive to keep ventilation rates down.

From inspection, many areas of typical nursing homes, including corridors and large common spaces, are not directly ventilated or are very poorly ventilated. The odour sometimes associated with nursing homes, which is a concern for residents and their visitors, is probably linked to poor ventilation.

Carbon dioxide levels sound a warning

Carbon dioxide levels in a building are a close proxy for the effectiveness of ventilation because people breathe out CO₂. The National Construction Code mandates CO₂ levels of less than 850 parts per million (ppm) in the air inside a building averaged over eight hours. A well-ventilated room will be 800ppm or less – 600ppm is regarded as a best practice target. Outside air is just over 400ppm

An RMIT team led by Professor Priya Rajagopalan is researching air quality in Victorian aged care homes. She has provided preliminary data showing peaks of up to 2,000ppm in common areas of some aged care homes.

This figure indicates very poor ventilation. It’s more than twice the maximum permitted by the building code and more than three times the level of best practice.

Research from Europe also indicates ventilation in aged care homes is poor.

Good ventilation has been associated with reduced transmission of pathogens. In 2019, researchers in Taiwan linked a tuberculosis outbreak at a Taipei University with internal CO₂ levels of 3,000ppm. Improving ventilation to reduce CO₂ to 600ppm stopped the outbreak.

Read more: How to use ventilation and air filtration to prevent the spread of coronavirus indoors

What can homes do to improve ventilation?

Nursing home operators can take simple steps to achieve adequate ventilation. An air quality detector that can reliably measure CO₂ levels costs about A$200.

If levels in an area are significantly above 600ppm over five to ten minutes, there would be a strong case to improve ventilation. At levels over 1,000ppm the need to improve ventilation would be urgent.

Most nursing homes are heated by reverse-cycle split-system air conditioners or warm air heating systems. The vast majority of these units do not introduce fresh air into the spaces they serve.

The first step should be to open windows as much as possible – even though this may make maintaining a comfortable temperature more difficult.

Read more: Open windows to help stop the spread of coronavirus, advises architectural engineer

Creating a flow of warmed and filtered fresh air from central corridor spaces into rooms and out through windows would be ideal, but would probably require investment in mechanical ventilation.

Temporary solutions could include:

industrial heating fans and flexible ventilation duct from an open window discharging into the central corridor spaces

radiant heaters in rooms, instead of recirculating heat pump air conditioners, and windows opened far enough to lower CO₂ levels consistently below 850ppm in rooms and corridors.

The same type of advice applies to any naturally ventilated buildings, including schools, restaurants, pubs, clubs and small shops. The operators of these venues should ensure ventilation is good and be aware that many air-conditioning and heating units do not introduce fresh air.

People walking into venues might want to turn around and walk out if their nose tells them ventilation is inadequate. We have a highly developed sense of smell for many reasons, and avoiding badly ventilated spaces is one of them.![]()

Geoff Hanmer, Adjunct Professor of Architecture and Bruce Milthorpe, Emeritus Professor, Faculty of Science, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

If architecture is the canary in the coalmine, the outlook for construction is appalling

Architecture suffers before building does.

A survey of more than 450 architecture practices conducted by the Association of Consulting Architects finds that two thirds have lost more than 30% of their revenue, and eight in ten have had projects cancelled or put on hold.

Six in ten are relying on JobKeeper. Half have cut pay or working hours. Three in ten have stood down or sacked staff. Only 15% believe they have enough work to see out the year.

In total, the survey finds more than A$10 billion of projects have either been cancelled or put on hold, just among those responding to the survey.

John Held, the National President of the Association of Consulting Architects says

unless there is a more effective stimulus package for construction, the government will need to consider extending JobKeeper beyond its expiry in September to prevent the loss of many normally-viable architectural practices. Without a pipeline of projects, a substantial rise in unemployment across the whole construction sector will result

Dr Peter Raisbeck, an expert in the building and construction industry at the University of Melbourne, says

two thirds of architects in Australia are small businesses employing less than five people, operating on small profit margins. Widespread insolvencies amongst these vulnerable firms would be catastrophic

The design professions – architecture and engineering – are the canary in the coalmine for the wider construction industry. If those professions are in a slump now, construction itself will most probably be in big trouble in three to six months.

A window on the future

The findings are reinforced by forecasts prepared by the Australian Construction Industry Forum.

They show that while engineering construction on projects such as motorways and public transport is likely to hold up reasonably well, residential and non residential construction, already weak prior to COVID-19, is set to slump over this year and the next, with the brunt of the impact being felt in NSW and Victoria.

It will be very bad for employment.

The building and construction industry consists of nearly 400,000 businesses that directly employ more than 1.2 million Australians. Most of the supply chain for building materials is in Australia, particularly for low-rise residential buildings.

The immediate priority should be to ensure that projects continue to be designed and documented to avoid the “valley of death” caused by the need for drawings to be completed before construction can start.

We’ve had warning

If eight out of ten architectural practices have projects that have been cancelled or put on hold now, there will be a significant shortage of projects going to tender later in 2020 and in 2021.

Based on the numbers in the surveys, the loss of jobs in construction could add two percentage points to unemployment during 2021.

To overcome the valley of death, something needs to be done to restart projects that have been deferred or cancelled.

To their credit, state and territory governments have brought forward varying amounts of public works projects, including schools, hospitals and a small amount of social housing. In Victoria, the acceleration of the government’s combustible cladding replacement program is also helping to prop up demand.

Unfortunately, the evidence from the Association of Consulting Architects survey suggests this won’t be enough.

Read more: HomeBuilder might be the most-complex least-equitable construction jobs program ever devised

HomeBuilder, the federal government’s $680 million program intended to “save the tradies”, appears to have stalled.

So far, none of the states has finalised an implementation plan for the scheme, perhaps because it was so poorly designed.

In Sydney, where a lot of houses may exceed the $1.5 million value cap, some builders are complaining that the scheme is actually delaying decisions while homeowners wait to see if it will apply to them.

And we know what to do

We can learn from history. The Rudd government’s $3 billion (in today’s money) Building the Education Revolution scheme was successful in stimulating construction and delivering jobs during the global financial crisis.

The $3 billion Home Insulation Program (later known as the “pink batts” program) also created jobs.

Although there was widespread and justified criticism of how both programs were implemented, they were big enough and quick enough to make a difference to employment. And they delivered general benefits.

We should be able to learn from these ideas and the mistakes that were made in their implementation.

Read more: What'll happen when the money's snatched back? Our looming coronavirus support cliff

The Morrison government’s efforts to support the construction industry to date have been too small and too slow. The architects survey suggests the design professions will go over a cliff in September. The construction forecast suggests that the construction industry will follow them over in 2021.

State and local governments have a long list of useful school, health and community projects that could go ahead now if the federal government made the money available.

Many shovel-ready projects that have been cancelled are in the higher education sector, many of them meant to deliver the STEM graduates or STEM research that the government says it is keen on.

There is also a crying need for good social housing, made more apparent by developments in Melbourne.

If we learned anything from the global financial crisis, it was that going hard and early worked. It is not too late to do it now, but it will be soon.![]()

Geoff Hanmer, Adjunct Professor of Architecture

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

HomeBuilder might be the most-complex least-equitable construction jobs program ever devised

HomeBuilder is a good idea gone bad. It is possibly the most complex and least equitable program the government could have devised to deliver construction jobs.

It gives $25,000 to people who already own a home or already have enough money to buy one while delivering a minimal stimulus to extra construction. It isn’t a program to create jobs, it is a way of making people who are reasonably well off richer.

It does not address homelessness, precarious rental or any of the other pressing problems that are caused by our current housing mix.

It might build more nice decks for sipping Chardonnay (most already planned), it might deliver ritzy new bathrooms with imported taps or even new kitchens with the latest European appliances, but it won’t help those suffering housing stress.

Read more: Scott Morrison’s HomeBuilder scheme is classic retail politics but lousy economics

Construction is Australia’s third-biggest employer, after retail and health care and social assistance. It employs one in every 11 Australians, and it generates other jobs in the building supplies industry and in design and engineering.

The Master Builders Association says construction is facing a decline of 40%, with potentially horrendous implications for employment.

The industry has three main components:

residential – apartments and houses

commercial – including offices, airport terminals, retail, tourism, education and factories

engineering – including roads, railways and airport runways.

Engineering construction is doing reasonably well.

Across the country, governments are delivering a veritable infrastructure Utopia. Continuing projects include the Tullamarine Airport Rail Link, the second stage of the Sydney Metro, the North East Link motorway in Melbourne, the WestConnex motorway in Sydney, the Airport Metro in Perth and Cross River Rail in Brisbane.

All governments have to do is keep this pipeline going, which, by and large, they are doing.

On the other hand, commercial construction will be in deep trouble by the end of the year as current projects finish without new projects to replace them.

Outlook bleak, then COVID

The outlook for residential construction is desolate, although for some people with secure jobs working from home, COVID-19 appears to have ignited a mini home renovation boom.

Prior to COVID-19, commercial construction was forecast to shrink from A$48.77 billion in 2020-11 to $41.3 billion in 2023-24.

Residential construction was forecast to bottom out in 2021-22 with only 168,000 dwelling starts, down from a peak of 233,872 starts in 2016-17.

Now, both forecasts will be slashed.

The tourism sector is dead, the education sector is near death and the multi-unit residential market, already badly impacted by confidence issues around construction quality, is in terrible shape with many projects on hold.

Not big enough, not broad enough

The HomeBuilder scheme is not big enough or broad enough to do much to reignite residential construction. To be useful for jobs, it would need to deliver an extra 60,000 housing starts.

Given the only people who will benefit from the grant will be those some way down the track to either buying or building, it is hard to guess what the additional outcome will be, but it would be surprising if the scheme generated much additional activity.

Even if the full budget allocation of the scheme is taken up, it would fund only about 25,000 projects. Many would have gone ahead anyway.

Among the peculiarities of HomeBuilder are that it won’t work in much of Sydney where many houses are likely to be valued above the $1.5 million limit and it won’t work in regional towns where the required spend will overcapitalise existing houses.

Complexities aplenty

It will encourage people to build in fridges, microwaves, coffee makers and washing machines (many of them tastefully European) to bump the contract price up above the $150,000 minimum.

It is a potential administrative nightmare for state governments that are already stretched administering existing emergency relief programs.

Who will establish that the value of an existing house is less than the $1.5 million upper limit? Will it be the value now in the middle of the COVID downturn or the value last year, or the value used to set local government rates?

Contracts are meant to be arms-length, but who will ensure the builder is not the cousin or the in-law of the owner, something that might be impossible to avoid in a small country town? If a garage is built on the side of a house, rather than as a separate structure, will it comply with the rules? And on and on and on.

Few extra homes

While these are legitimate questions, they ignore the big, central problem with the scheme: the opportunity to deliver a substantial program of social housing that would address real problems, including homelessness, has been missed.

And the government has done it in a way that will minimise the jobs created and maximise the wealth transfer to Australians who are relatively well off.

For a government that has mostly managed to do the right thing ever since COVID-19 hit, this has been a terrible policy clanger.

It will encourage everyone who cannot afford to buy a home, or who is homeless, to believe the government has forgotten them.

Geoff Hanmer, Adjunct Professor of Architecture, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No big packed lectures allowed if we're to safely bring uni students back to campus

A return to face to face teaching at universities and technical colleges “where possible” is one of the goals of the Morrison government’s three step framework for a COVIDsafe Australia.

A look at the space available for teaching shows some return of students is possible.

But nearly all tiered lecture theatres will not comply with the social distancing rule of staying 1.5m apart, assuming they are seated at capacity. Those lectures will have to remain online or the rules around class sizes will need to change.

Back to the campus

Universities moved teaching operations off campus to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic. Many lectures and tutorials are now done online.

Universities have the challenge of working out how to safely get staff, students (and researchers) back to campus.

But the teaching space data from eight Australian universities reveals a number of problems in returning to campus while meeting social distancing rules. Some of these can be overcome, but others, including the key goal of increasing face to face teaching, will be much harder.

Until we reach Step 3, when up to 100 people may be permitted to gather in one space, opening up a campus is impractical. Under Steps 1 and 2 only 20 people are allowed in one space.

Come up to the lab

It should be possible to reestablish most laboratory based teaching and research to meet Step 3 guidelines without too many complications. The space data shows most laboratories provide about 4m² per person on average, although space between benches in some older labs may pose issues.

Where open plan offices are being used, they will have to meet social distancing rules.

Most university open plan offices have a density that is significantly lower than the 4m² average set by the guidelines, although achieving the 1.5m distancing rule may require some adaptations, such as additional screens.

Staff will be needed on campus as students return, but simple provisions similar to that used in retail shops, including floor signs and barriers, will be adequate to achieve the distancing guidelines. The continuing trend to move student services online will also help.

Cramped lecture rooms

Teaching space is much more problematic. The space data shows it is not possible to deliver conventional lectures in most existing tiered auditoriums during Step 3 restrictions. The absolute limit of 100 students in one space, narrow seat aisles and close seat spacing make them difficult to adapt.

Online lectures will still be necessary for the foreseeable future.

It is possible to deliver small group teaching, in groups of 19 to 100, but the space data we examined show only about one-third of non-lecture and non-laboratory teaching hours could be delivered on campus across a typical 50-hour week.

The smallest room that could accommodate a group of 19 students and an academic is 80m² under Step 3 guidelines. Only about 20% of campus teaching spaces are big enough although this percentage does vary from campus to campus.

Successfully delivering small group teaching will probably require a lot of work on existing course structures and plenty of furniture relocation. But the opportunity to provide this type of teaching to the limit of capacity will be valuable in supporting retention and improving student experience.

Students love campus life

A campus is the largest capital investment a university makes and there are valid reasons why this is so. Attrition, retention and student experience data all suggest face to face teaching and other aspects of campus life are effective ways to attract, engage and retain undergraduate students.

A campus is also essential to deliver laboratory-based research. STEM research accounts for the majority of university research income and delivers many useful things, including perhaps a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.

The timing of Step 3 is in the hands of state governments. For example, Queensland says it will move to Step 3 on July 10 while Tasmania has chosen July 13.

By the start of Semester 2 in late July or early August, it is probable that most states will have moved to Step 3.

UNSW, which moved to a three term model last year, will commence Term 2 on June 1, too early for Step 3.

Getting to campus

Another challenge though for universities is that of getting staff and students to campus on time. The capacity of public transport has been severely reduced by social distancing rules under Step 3.

Read more: Universities need to train lecturers in online delivery, or they risk students dropping out

In many cases it will not be practical to operate a campus with a full student or staff load.

Because campus populations are likely to be considerably reduced for a significant period of time, the challenges currently faced by on campus shops, food outlets and recreational facilities will continue.

The faint silver lining to all of this could be a long-term shift towards small group teaching, supplemented by high quality online materials, rather than reverting to the large lecture as we knew it.

Geoff Hanmer, Adjunct Professor of Architecture, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Why the focus of stimulus plans has to be construction that puts social housing first

Australia has done better with COVID-19 than anyone dared hope. This opens up the prospect of a progressive relaxation of restrictions later this year. Organisations that could participate in an economic stimulus program will need to be in a position then to deliver “shovel-ready” projects to help revive the economy.

The construction sector is the obvious focus of a stimulus plan, and the construction of social housing should be the priority, for reasons that I’ll outline below.

Read more: Is social housing essential infrastructure? How we think about it does matter

The Rudd government’s stimulus package during the Global Financial Crisis gives us a helpful guide to what does and doesn’t work. The initiatives that failed did so because of a lack of proper planning.

Fortunately, if we get going now, we have months to plan the recovery program. Getting it right will be crucial. By September, one month before JobKeeper payments end, many businesses are going to be on their knees.

Why construction?

Most of the successful elements of the Rudd package focused on construction. The reason is simple. Nearly one in ten Australians work in the construction industry. Many more are employed locally in the production of building products.

Both construction and building product manufacturing provide jobs for people with varying levels of skill, including people who are unskilled. The vast majority of concrete and steel reinforcement, bricks, wall framing, building boards, windows and doors, roof tiles and metal cladding are still made here. A substantial portion of domestic electrical and plumbing products, including stainless steel sinks, copper pipes and electrical cables are also made here.

It’s important to realise that the type of building being constructed will affect its local stimulatory impact. For buildings up to three storeys high, over 50% of their cost is labour on site. Of the remaining cost, the vast majority is Australian-made materials and components. (Although the Australian Bureau of Statistics stopped its series on Australian-made construction products in 2014, the employment impact can still be estimated from ABS manufacturing statistics.)

However, the taller a building gets, the greater the percentage of imported components – lifts, mechanical components and facade systems are mostly imported.

Why social housing?

What sort of construction projects should the government consider for a stimulus package? While the response so far has been to focus on “fast-tracking” infrastructure, the current crisis has highlighted a number of pressing social needs. Various aspects of social housing top the list:

Housing to reduce the number of people living in precarious private rentals. A substantial program to increase the stock of social housing would be a great legacy.

Housing for people who are homeless. They will not be able to go on living in hotels once the lockdown ends.

Affordable housing for workers in health, emergency services, education and retail who cannot afford to live close to the communities they provide vital support to. It turns out they are essential workers, some of the most important people in Australia, so we need to look after them.

Housing construction is a very effective way to create jobs, both directly and downstream. About 6% of Australian jobs are related to housing.

What other construction work is needed?

There are other opportunities for well-targeted construction stimulus.

In many areas of Australia, public schools and kindergartens still rely on low-quality portable buildings or buildings that have exceeded their economic life. A program to replace them with new and efficient buildings would produce substantial social benefits, cut maintenance costs and improve sustainability.

Improving the deteriorated state of community buildings and parks, particularly in disadvantaged areas, would also deliver social benefits and potentially employ a lot of unskilled labour. Having decent parks and exercise facilities close to where people live will allow social distancing to continue as long as needed.

A Victorian government plan to remove combustible cladding from residential and community buildings could also be extended to all states. It’s essential work that would also create jobs.

Read more: Flammable cladding costs could approach billions for building owners if authorities dither

The government could also consider a program to replace or refurbish university teaching and research buildings that are over 40 years old. Incredibly, as we have found at ARINA in our consultancy work, these older buildings still provide more than half of the 11.8 million square metres of gross floor space occupied by the higher education sector.

These ageing buildings are not well suited to supporting the research into solutions to SARS-CoV-2 and other pressing medical and economic problems. Replacing or refurbishing them would improve outputs, cut maintenance costs and improve sustainability, plus give a much-needed boost to the higher education sector.

Plan now to be shovel-ready

Anglicare SA is already thinking of what it can do to deliver more social housing. Its CEO, Peter Sandeman, told me he is making sure Anglicare has “shovel-ready projects that can be rolled out the moment a stimulus package is announced. There is no better way of stimulating the economy than by constructing social housing.”

This is stimulus that also meets critical social needs, Sandeman says.

There is a desperate shortage of social housing. Our waiting list and the number of people who are homeless demonstrates that.

Social housing provides a long-term benefit to everyone. It adds stability to the lives of the occupants and this is a particular benefit to their children and their education. Safe, affordable housing is the foundation stone that gives people a chance in life.

Other organisations that could be part of the stimulus package should be getting ready, too, and making sure the government knows what they are doing.

Read more:

Australia's housing system needs a big shake-up: here's how we can crack this

![]()

Geoff Hanmer, Adjunct Professor of Architecture, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Automatic doors: the simple technology that could help stop coronavirus spreading

New research in the New England Journal of Medicine suggests that SARS CoV 2, which causes the disease known as COVID-19 coronavirus, is more stable on plastic and stainless steel than on cardboard or copper:

The longest viability of both viruses was on stainless steel and plastic; the estimated median half-life of SARS-CoV-2 was approximately 5.6 hours on stainless steel and 6.8 hours on plastic"

This is disquieting news for building designers and the manufacturers of door hardware and taps, who have traditionally used stainless steel or chromed brass under the common (but incorrect) impression that they provide an unfriendly environment for bacteria and viruses.

They are certainly relatively easy to clean, at least visually, but taps and door pulls in public toilets and door hardware in apartment common spaces and lift buttons are not cleaned between every use.

With this in mind, it is concerning to see just how many doctor’s surgeries and dedicated coronavirus facilities in Australia and elsewhere still appear to be equipped with manual hinged doors with stainless steel or chromed brass handles and push plates, both inside and out.

Doctor’s surgeries have door handles

It is clear from the available research that this type of touch point poses a risk of transmission, particularly in placers where a significant proportion of users will be ill with a virus, if not SARS CoV 2.

Door handles, door pushes, lift buttons, flush buttons, taps and hand dryer buttons are all typically made from hard materials including stainless steel and plastic.

While SARS CoV 2 is a uniquely hazardous bug, other common viruses and bacteria, including the common cold and the rotaviruses that cause gastro-intestinal infections are also transferred by touch points in buildings.

This is completely unnecessary given that we have simple technology available to obviate the problem.

Automatic doors are cheap and safe

While the lifts and reinforced concrete were probably the most significant technical developments for buildings in the nineteenth century, the development of a reliable automatic door was, alongside mechanical air conditioning, among the two most significant technical developments for buildings in the twentieth century.

Similarly, we now have reliable technology to automatically flush toilets, dispense hand wash and operate taps.

Even if we can’t afford an automatic door on the outer doors of public toilets, the least we can do is plan the doors to open outwards so the doors can be opened with our elbows, or eliminate the doors entirely by making the entrances U-shaped.

Our reluctance to install them is odd